- Home

- Alex Laidlaw

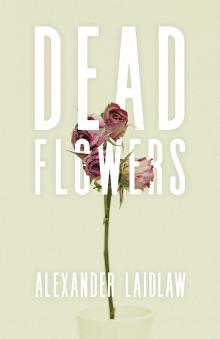

Dead Flowers

Dead Flowers Read online

Dead Flowers

Stories

2019

Copyright © Alexander Laidlaw, 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency, www.accesscopyright.ca, [email protected].

Nightwood Editions

P.O. Box 1779

Gibsons, BC v0n 1v0

Canada

www.nightwoodeditions.com

cover design: Topshelf Creative

typography: Carleton Wilson

Nightwood Editions acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, which last year invested $153 million to bring the arts to Canadians throughout the country.

Nous remercions le Conseil des arts du Canada de son soutien. L’an dernier, le Conseil a investi 153 millions de dollars pour mettre de l’art dans la vie des Canadiennes et des Canadiens de tout le pays.

We also gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Government of Canada and from the Province of British Columbia through the BC Arts Council and the Book Publishing Tax Credit.

This book has been produced on 100% post-consumer recycled, ancient-forest-free paper, processed chlorine-free and printed with vegetable-based dyes.

Printed and bound in Canada.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: Dead flowers / Alexander Laidlaw.

Names: Laidlaw, Alexander, 1985- author.

Description: Short stories.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20189047887 | Canadiana (ebook) 20189047895 | ISBN 9780889713550 (softcover) | ISBN 9780889711457 (ebook)

Classification: LCC PS8623 A3938 D43 2019 | DDC C813/.6—dc23

in time I will offer one book dedicated

to each and every person I love

as for this book

it doesn’t seem right for them

so I give it to the past, wherever it went

Contents

Dead Flowers 9

One Time I Witnessed a Murder 13

On Gordon Head 28

You’re Getting Older 47

About Franklin 56

War Story 100

Then She Smiled and Walked Away 139

The No-Cry Sleep Solution 149

Acknowledgements 171

About the Author 173

Dead Flowers

It was three o’clock in the morning when I finished a second draft of my letter to Councilman Kane, written because I’d read recently in the news that his wife was dead. It’s such a shame, I wrote. She was just such a beautiful woman. I mean, besides whatever else she must have been. The truth is, I had only ever seen her photo in the papers. But councilman, it pays to see the good in a bad situation. The whole wide world thinks life is cheap, and really that’s the only way to think of it. In the end we are better to have thrown it off. Better that she was able to do it on her own terms and in her own time. At the end of the letter I signed off saying, Up, up and away! After that I fell asleep, sitting upright in my chair.

When I awoke it was morning, and I found myself lying in bed. And it’s for reasons like this that I hate this utterly miserable time of the year. Nothing holds together or makes any sense. Everything starts to unravel. I can’t even hold myself together, as every thread is now cut so that I can’t even trust I’ll wake up in the place where I fell asleep.

After waking I lay in bed for hours doing nothing, like a rabbit, with my head in my hands. For hours I looked at the window. Outside the rain was falling, and every so often a little black bird flitted in and out of view. Grape vines, already wasted by the cold, still clung to the garden trellises.

Earlier, Joe had had his friends in for coffee, and there’d been a ruckus above. I knew all about it because of my dreams. It had been the end of the Second World War. Grizzled voices shouted in broken English over the radio. Eyes blinded in a smoke of cigarettes. Tears were shed. There was a tumbling down the stairs. I dreamt of Joe standing under the window, yelling to someone, saying something about plums. He held a pyramid of golden-purple plums in his outstretched hands. But his hands were, as always, covered in dirt. And Joe was, as always, drunk. Coffee in the morning meant three fat fingers of rum spilled into every cup. It was the same thing every Wednesday, he and his friends starting in around seven o’clock.

But don’t you think of judging him. Not anymore, you haven’t the right. You forfeited that when you left and forgot that Joe was here, was still alive, still putting in hours, still shaking his legs. Just as you forgot this house, this room, this bed, all now still as it was.

By the time I was up, his friends had gone and in all probability, Joe had taken a bus downtown to wet his whistle at the Old Tin Flute, or the Legion, or the Barrel & Bull. And that’s another thing I just can’t stand about this time of year: the silence, with no sign of life. Only dozens of pots and pans laid out in the yard to catch the rain. And the hot sound of blood roaring in my open ears like a ringing of bells. Which is maybe why I’m writing these letters, these words. Because I do get lonely, understand? And I go crazy with this loneliness. I get out of bed. I take out the trash. I eat a piece of buttered toast with coffee. I go outside to smoke yet another cigarette, standing in the cold, and I wander barefoot up and down the muddy byways of the garden.

Every year Joe tends his garden. He grows an array of both flowers and food. Every year he overwhelms his neighbours and friends with apples, plums, figs, onions, beans, peas and bunches of kale. But then every year, around this time, the garden up and dies. It leaves him and he flounders. And every year he flounders just a little further off.

I ask him what that’s like.

He says, It’s exactly like I lost my wife.

More than anything else he misses the flowers, he says, and wishes every year they’d be a bit quicker coming back.

But Joe isn’t sentimental. He wears a baseball cap that reads, Old as Dirt. All day, every day, he walks around town drunk, his zipper collapsed, and with the soiled tails of his shirt sticking out like a tuft of feathers from the seat of his pants. He calls me a son of a bitch and asks, Don’t you ever get tired of fucking only yourself? Then he boasts that he’s been growing food for over seventy years, ever since he was nine. I know everything there is to know, he says, his face right close to mine.

It’s a story I have heard before, at least half a dozen times. About how his father left to fight in the war, and his brothers left to fight in the war, and the war raged all around, to east and west and north and south. So Joe had to learn to work the land or else see himself, his mother and his sisters starve. In fact, the only piece of the story I had never heard before was something Joe told me this afternoon, about how one of his brothers never came home. According to the army, the brother’s body was lost, and the only thing the family ever had of their fallen son was a postcard. It came by mail on a day many months after the boy was supposed to have died. It was addressed to the mother, saying only, I miss you darling, please come home.

I said to Joe, That doesn’t make sense.

Then he started in asking for rent.

Tonight I sit at the desk, staring into the distance, through the walls and into the night. All around me are scattered pages, the detritus of so many nights I have spent this way. Old ideas and worthless thoughts. Letters that will never be written. Letters written that will never be sent. And all the while I know that the only thing I ought to write, that the one and only thing that could make any difference anymore, would be a letter to you.

I pick up a pen, but not

hing comes to mind. Well, it isn’t nothing, only it doesn’t really make any sense. I mean, it isn’t something you’ll understand, not now that our lives have split and have come undone and we find ourselves so far apart. You won’t understand. You will think one thing, but the truth will be something different. Still, there are no other words I can write.

So I bend myself one more time into the task. I scratch a few words onto the page. Single draft. I’ll send it in the morning. I miss you darling, please come home.

One Time I Witnessed a Murder

It seems like such a while ago now, but it still comes up in conversation—around the table at a dinner party for instance—and then whoever hasn’t heard the story before will want to hear it, and those who have heard it will want me to tell it again.

All eyes on me, I’ll reach for a bottle of wine to fill my glass. I don’t want to tell it again. I’ve told this story so many times over the years, but I’ve never felt I got it right. You just can’t talk to people and tell them the truth. Not around the table at a party. Not after so many glasses of wine.

I was a student on summer break after my second or third year at university. I get mixed up remembering the timing, but at any rate it was the summer I decided that from then on I was only going to be a student part-time. It would take me a little longer to earn my degree, but that was fine. What was the point, anyway, of working so hard to finish school? Four years of hard work to be followed by what? Hard work the rest of your life.

I didn’t even have a job at the time. Until recently, I had been a cook at an upscale Italian place, but then one day I simply walked out. Actually, what happened is I got drunk one night and then slept through my morning alarm. By the time I woke up, I had missed my shift, so I never went back.

My girlfriend was having her doubts about me. We were supposed to take a trip that summer. We’d talked about going to Portland, or maybe north to the Yukon to camp. We hadn’t yet figured it out, but when a friend of mine offered me a ride to the Calgary Stampede, saying that he also had a place for me to stay, I said I would go. There wasn’t any room in the car for my girlfriend, but I failed to see the connection between this development and our nascent plans. She was angry with me when I told her the news. This means we won’t take a trip of our own, she said.

I said, Ayleen, the summer is long. There’ll still be plenty of time for us to get away.

But you won’t have any money, she said.

Well, I couldn’t argue with that.

That summer, she and I were living together—though it is more accurate to say I was living with her. The room had been Ayleen’s before I had come, and it would be hers again after I left. I kept all my things in a very neat pile apart from everything else in the room. But we did have a cat together, sort of. The cat had belonged to somebody else in the building but was neglected. Ayleen and I had taken to feeding the poor thing, so finally the little beast came to live in our room.

And we had a nice little life together, I thought, she and I and the cat in that room. I would open the door onto the balcony to let in the air and the light. Ayleen would dangle a bit of yarn for the cat. The cat would jump, and I would take a picture of that—her legs and the light and the cat and the yarn.

But then I went away to Calgary and was drunk for three days and nights. Ayleen planned a trip of her own to visit family and friends up the coast. When I got back, she was already gone.

I woke up, and it was already noon. I made a cup of coffee and took it on the balcony. Our railings were overgrown with vines coming up from the garden below. Some of it was clematis, but mostly morning glory. It was mid-July and those flowers had started to bloom. It never rained much during the summer, so lawns throughout the city were scorched. It was sunny almost every day and hot, but at night a chilling moisture would descend.

And that was that city—that was July.

This is the story I don’t ever get to tell. These are the poignant details, not about the body, not about the blood, but the real and significant-or-not details I never get to mention. Like how on that first day without her I didn’t eat breakfast but had a coffee then drank a beer. I immediately felt guilty for drinking the beer. I felt as if someone was watching. I felt as if I might get caught.

But at least I hadn’t planned on drinking a beer after coffee that day. I had simply been going through my knapsack and had found a can of lager left over from Calgary. So I drank it and then felt ashamed. I felt shaky and even slightly buzzed. I felt terrible actually, miserable, and I thought I should eat something but I had no appetite. So instead of eating I rode my bicycle downtown, parked it at the library and spent the rest of that day hiding out in the stacks, covering my many moral failings with a conspicuous effort to expand the horizons of my learning.

Later that night I wanted to write. I felt I had to organize the contents of my head. I was sick at heart, which in those days always led me to paper and pen. I cleared a space for myself at Ayleen’s desk. It was dark outside and I could see the reflection of myself in her bedroom window. I set out my notebook and pen. I made a coffee to keep myself awake.

I’m in love with a woman who doesn’t love me, I wrote, because that was what seemed to be true. There’s probably some other man in her life. Someone to indicate all of my faults. Or worse, someone to forget me by. She’s felt drawn to him and was for a time so loyal to me, she didn’t recognize her feelings. Lately though, more so, she thinks about him. It’s probably someone she knows from work.

I put down my pen and thought of Ayleen and the place where she worked. It was an organic market downtown, and she worked as a server in the deli there. She hated her job—or was she fond of it? I suddenly realized that I didn’t know. And I felt like a terrible boyfriend, being unsure about this pivotal fact.

I picked up my pen.

While I’d been away, Ayleen had gone out one night with her friends from work. They’d all gone to a bar to see some show, and of course the man in question had been there. Probably there had been dancing, first part of a larger group before the two of them found each other, gradually, each little step taken toward one another, each unremarkable if considered alone. And probably he had walked her home. Same thing—beginning with five or six individuals heading northeast, leaving downtown, then each of the others falling away until the two of them stood at the swinging iron gate at the foot of our stairs.

I wrote this as I imagined it could have happened. Nothing outrageous at first. She stands on the bottom stair, turns to him, says, Well, goodnight? I recorded the rise of a blush, not in her face but in the upper pallet of her breasts. Her blush for knowing, even if not admitting yet, the thing this all was building toward. He watches her legs on the stairs. She moves slowly, giving him the pleasure of this, teasing him, drawing him on. Slowly, taking me hours to get to the place of her body and his in our sheets.

Why? would be a reasonable question. Why would I want to create such a scene? Because I was feeling shaky, uncertain, unwell and I wanted to make myself crazy that night. And I did go half-crazy that night, laying her to bed with another in prose.

The next day, I woke up around noon. I made a cup of coffee and took it on the balcony.

Now, if I could truly tell this story how I wanted, I would want to take a few moments here to talk about something else entirely.

I remember the cat was called Munich, but we wanted to change its name to Munch, after the artist Edvard Munch. I wasn’t a fan of Munch and as far as I know, neither was Ayleen. But some weeks before we abducted the cat, we’d found a Norwegian film about the artist at the library and brought it home to watch it one night. It was such a long movie, and so terribly slow and strange. Every so often a character would break from their scene and look directly at the camera, at the viewer. It was disconcerting, as if something had been said that we hadn’t understood and now a response was demanded of us.

The movie was so long that we had to take a break midway through. We had to walk to the

store and back to stretch our legs and to fortify ourselves with a snack before braving the second half. It was probably three o’clock in the morning by the time we finished it and I don’t know why, but we were wired, wide awake, full of a nervous energy. Was it something in the subject of the film that had infected us? Or was this simply an effect of having been held for so long at the pace of the film that we found ourselves with an untimely quantity of pent-up energy? We didn’t know what to do, but knew we had to get out—out of our bed, out of the room, into the city and into the night. We tied up our laces and left, and that night we walked together and talked for three, four, five, six hours. God knows. We got back to the room and fell into bed and made love until both of us slept, even into our sleep trying to continue the act.

So of course we wanted to change the name of the cat from Munich to Munch. We wanted that cat to be a reminder of just what we were, what we meant to each other. Because yes, we were in love, but we were also so painfully, stupidly young.

The first three days I was alone, and every night I was alone. I didn’t go out, didn’t see anyone. I was up late sitting at Ayleen’s desk, writing out terrible things. About her giving herself to him in ways that the rote of our relationship prevented. About her being lost in him, growing in new directions through a process of abandon, moving into spaces I could neither provide nor follow her into to witness this growth. I made myself sick and aroused writing about her and this man, this unknown man, this man I had never met, this man who in hindsight likely didn’t exist.

Then it happened—this murder, the so-called main event. It occurred at the end of a long night wherein I had gotten drunk at a birthday party. My friend Miller had turned twenty-two and he hosted a barbecue to celebrate. I went along more or less for a change of scenery, to get out of her room and away from myself and the rut I had been digging.

Miller lived in one of those rental houses so common around colleges and universities. An old Victorian home carved into so many bedrooms, that had been allowed to slide into disrepair. There were ten to twenty people in every room of the house, wearing shoes and tracking dirt onto the carpets, spilling drinks and leaving half-finished food on tables, shelves and a mantle in the hall. I got drunk off a bottle of wine and then went around picking up stray cans of beer.

Dead Flowers

Dead Flowers